A Short History of Fly Fishing in Algonquin Park

Agents of change

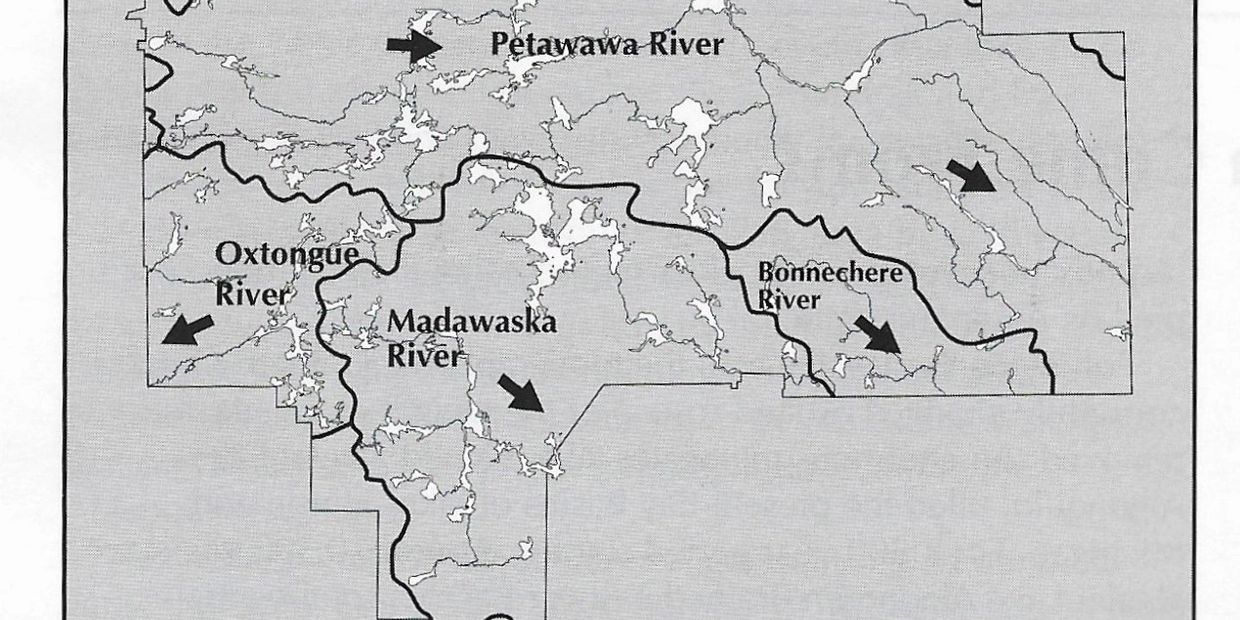

Algonquin Park is Canada's oldest provincial park, established in 1893 to protect the vast upland white pine forests and the headwaters of six major river systems. At 7,653 square kilometers (772,300 hectares), this is a huge wilderness area. This park status, and the unique geography and history, all become the ingredients for this special and unique fishing destination. Below you will find an overview of the park’s geography and human history, and how that has influenced the brook trout and bass fishery, and the relatively unsung fly fishing history of the region.

There have been a small handful of agents of change that have played a big part in shaping Algonquin Park and its fishery. The most predominant was the last ice age. Up until 11,000 years ago the region was covered in ice up to two kilometers thick. As the ice sheet slowly retreated north, massive amounts of fresh water flowed to the ocean. The weight of ice depressed the landscape, so the most direct path from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean was via the Madawaska and later the Petawawa Rivers, both dumping into the Ottawa River and onward to the sea. The Atlantic Ocean itself pushed up into the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Valleys, given the depressed land surface, which slowly ‘rebounded’ (albeit over thousands of years!), raised up and pushed the sea downhill. Around the Ottawa Valley there is a ‘bath tub ring' of beautiful, sandy beaches, the remnants of the ocean’s shoreline and the glacial outflow. We camp on a couple of these on our multi-day drift boat fishing trips.

The ice age scoured the landscape and pushed most of the soil into southern Ontario, leaving behind the iconic rocky peninsulas and highlands of Algonquin Park. The relatively shallow, sandy soil was ideal for white pine and mixed spruce forest/hard wood combination to populate the area. This shallow soil and predominance of pre-Cambrian rock makes for acidic conditions, detrimental for the brook trout population. Brook trout have a narrow window of ph in which they can thrive, and Algonquin Park’s ecosystem is at the lower limit. Brook trout thrive at a ph of 6.5-8.0, but can survive in a range of 4.0-9.5. Algonquin Park waters can average 4.5-4.8. This is one reason that fish density is low in the park i.e. there are fewer fish per acre of lake or mile of river than in many other locations.

As the land continued to rebound and rise, what was to become Algonquin Park grew to a height of land, and the headwaters of six major rivers systems (see the map image at the top of this page). The central and eastern part of the park drains east to the Ottawa River, while the west side drains to Georgian Bay and the Great Lakes. Brook trout, well known as not a trout at all but a cold water char, followed the melting ice sheet and the new river systems, eventually populating all of Algonquin and northern Ontario. There are hundreds of lakes and streams left behind, now the largest concentration of brook trout habitat in the world. In the park itself, 230 lakes are listed as containing brook trout populations (and therefore are in all the streams that connect those lakes).

The second major agent of change has been humans, in particular the railroad. At some point after the ice sheet retreated, the Algonquin Indigenous people returned to the area, living off the land and the rivers. But by the 1700’s, introduced disease, tribal warfare with the Iroquois to the south, and just being pushed out by European settlers, logging, and diminished wildlife resulted in them being pushed to the further reaches of the Ottawa River watershed. The wider Algonquin region is the unceded traditional territory of the Algonquin people, with a modern land claim in the works for the past many years.

Europeans first trapped beaver extensively across all of Canada, and then proceeded to log the famous virgin white pine forests, with giant trees that were hundreds of years old. Algonquin Park was created at the urging of the ‘Lumber Barons’ in order to protect the valuable forests from fire and the rivers from degradation – both the natural resources they relied upon to get rich. The many dams still present in the park were built to regulate water flows to help in moving logs downstream. Logging still continues to this day in Algonquin Park, albeit by a road network closed to public access.

More importantly to the native fishery, the railroad played a substantial role. In 1896, three years after the park’s creation, two railways were put through. One where Highway 60 now traverses the southern end of the park, and another specifically to facilitate logging that traveled up the Petawawa River and across the larger northern portion of the park. In less than three years (1899), the train was used to stock small mouth bass, not native in this upland cold water fishery. For context, this was the era of ‘man over nature’. All across North America fish hatcheries were pumping out millions of sport fish – primarily rainbow trout – and planting them in lakes and rivers across the continent. Rainbow and brown trout were planted in the park, too, but did not create sustaining populations and quickly died out. Small mouth bass were seen by park managers as a means to increase the size and catch rate over the native brook trout. It was not realized at the time that bass out-compete brook trout, and where bass thrive there will be no brook trout. This is the case on the Petawawa, where the lower reaches (below Poplar Falls) is now exclusively bass, walleye and musky – all introduced. Above the falls, brook trout still thrive, with the falls acting as a natural barrier. The small mouth bass range is limited, even today, to water near the (now removed) rail lines. Further with the fish stocking story, brook trout have been stocked in the park, according to park publications. During the stocking hay-day, Pennsylvania brook trout were planted in Algonquin Lakes. It seems intuitive, with today’s knowledge, to see that as a bad idea. The non-native fish have diluted the native stock with a less resilient strain, a point now well documented. A park newsletter article in 1995 (Vol. 36, No. 8) provides a map with which lakes and waterways still have native fish and which have a hatchery gene present, even now several decades later. Interior lakes are no longer stocked with any fish (although there is stocking along Hwy 60), and Algonquin is closed to fishing all late fall and winter – a management move that significantly protects the health and sustainability of these special native stocks. It is this native stock that make Algonquin brook trout fishing special.

The last agent of change to note is climate. Acid rain was a significant threat back in the 1980’s, but that seems to have stabilized. Recall the border line ph levels for brook trout; pollution and acid rain were pushing these numbers to the brink. Even today, mild pollution builds up in the snowpack over the winter. This accumulated acid gets rapidly flushed down the rivers in the spring melt, potentially creating deadly acid shock that compromises over-wintering eggs. Occasionally a whole year cohort will be affected with low egg survival, which means that in 2 or 3 years, when mature, the fishing will be less productive. For the future, warming climate means warmer water. Brook trout spawning beds require cold, clean water. Brook trout will be net losers in this game. Bass will have access to more water, being tolerant of and requiring warmer conditions.

Fly fishing has been a staple in Algonquin Park fishing from the beginning. As soon as the train lines pushed through the park in 1896, tourist hotels and lodges quickly followed. With them came ‘sports’ from the cities and a sizable guide culture to get them to the fish. Note that at the turn of the twentieth century, all fishing gear looked like current fly fishing equipment – the mechanics of the gear and even the tactics and casting itself is largely unchanged. In those days however, there were few purists. Most would throw a fly, hook a worm, or troll a homemade spoon – whatever worked.

Theodore Gordon, the grandfather of dry fly fishing, was just articulating his ethic and technique in New York’s Catskill rivers at this same time, and as the Catskills and Adirondacks became logged over and fished out, interest from the small group of dedicated artificial fly fishers spread north. The Dumoine River on the Quebec side of the Ottawa River and Algonquin Park became destinations. Joseph Adams, the influential English fly fishing writer, visited Algonquin in 1910. As recorded in Canoe Lake, Algonquin Park: Tom Thomson and Other Mysteries, ‘[Adams] hired park ranger Mark Robinson, an excellent man well acquainted with the forest, to guide him on an expedition to the Oxtongue River to fly fish for brook trout. He had great success […] catching trout with his ten-foot cane-built rod and gut casting silver doctor and march brown (artificial flies).’ The 1943 book The Incomplete Anglers (Robins) was based around an Algonquin Park fishing trip. It was a mainstream best seller at the time, and won Canada's most prestigious non-fiction writing award. It is interesting that the author relied upon gaudy traditional salmon flies for brook trout.

The famous Canadian artist Tom Thomson called Algonquin Park home in the summers, inspiring his extensive collection of likely the most famous paintings of Canada. He was an avid fly angler, although likely not dedicated solely to it (the most well published photo of him has him tying a spoon onto a fly line). He worked as a fire ranger and was a licensed park guide, before his mysterious drowning in Canoe Lake in 1917.

In those early days of Algonquin Park, park rangers and guides had an interchangeable role; they were locals with bush knowledge and fishing skills. Eventually the railway hotels and inns had full time guides; up to 140 guides lived in Whitney (east gate of park) at one time. Ralph Bice and Frank Kuiack spent their lives guiding solely in Algonquin Park, all the way from the 1920’s to the 1980’s (and are immortalized in print, Along the Trail in Algonquin Park (1980) and The Last Guide (2001)). Bice is attributed this memorable quote: “I don’t know if guides go to heaven, possibly they do. If they do there can be no doubt but what they will be disappointed, for no spot could be as nice as Algonquin Park.”

The advent of spin fishing after the World War Two certainly changed the way most people fished. Fly fishing is still the most productive way to fish brook trout in the spring and fall, when they inhabit the rivers and feed in the warm shallows of lakes. By summer, they move deeper into the lakes to find colder water. That’s why you hire a guide, to get you to the out-of-the-way places that hold brook trout. The bass fishing is stellar, given the low fishing pressure, no winter fishing, and the best fish on the whitewater rivers that keep 99.9% of the population away.

As a guide service we are 100% catch and release. The native brook trout are too rare and need protecting, and the bass we get you to are large and in their reproductive prime. We intend to keep it that way. It is disappointing that Algonquin Park management has not taken a firmer stand on catch and release. Their website and literature make the assumption you are going to kill what you catch (within license limits, I presume), romanticizing the 'shore lunch' and a string of brook trout. This is a cultural relic: fishing was targeted as the primary means of attracting tourists to the new park when it was created. You can find no shortage of photos from that era of 100 fish strung up at camp. I believe there is still some fear that stricter fishing regs that protect the fish population would adversely affect park permits and revenue.

The Friends of Algonquin Park have a number of publications to learn more about the park's fishery: link here (the map at the top of this page comes from their Fishes in Algonquin Park).

Algonquin Park's own fishing page: link here

Algonquin Park has one of the longest standing fresh water fishery research programs in the world. Much of what the world knows about lake trout and brook trout has come from the Harkness Lab of Fishery Research in Algonquin Park: link here

A summary of brook trout research can be found here.

Fly fish with us!

Algonquin Fly Fishing Premium Guide Service is Algonquin Park and the Ottawa Valley's premiere fly fishing guide service. As career guides and Ottawa Valley natives, we know east Algonquin's brook trout and bass fishing better than anyone. Drift boat day trips, multi day adventures, or learn to fly fish. Click below to learn more about what we offer.

Algonquin Fly Fishing